The minister of finance, Tito Mboweni, delivered the medium term budget policy statement for October 2019 last week. The minister correctly pointed out that the medium-term budget is not the main budget, which is normally delivered in February each year.

Given the gravity of the fiscal situation and weak economic performance of the local economy however, it is understandable that much was expected from the October budget. The budget, unfortunately, was rather lacklustre and disappointing. The hard reality that the budget is pointing to, is that politics is presently trumping efforts at meaningful reform.

Sakeliga’s initial reactions to the budget are presented in the following media statement.

The minister, apparently, could only move within a narrow range of current political constraints. The national budget, we have to remember, is not a proclamation, but a document parliament has to agree on and accept. Efforts at reform, it seems, are stuck in a highly dysfunctional inertia.

Effective reforms, at this dire point, require a serious drive towards market freedom, deregulation and a down-scaling of the State’s extensive involvement in and say over the economy. Despite statements on intended reforms, many government departments are still floating bills, policies and regulations that run counter to market freedom.

For example, the tourism department seeks to regulate short-term home rentals and Human Settlements wants further central regulation of home builders. The economic development department seeks measures for stronger competition intervention – even along the lines of race-based empowerment.

Even if Minister Mboweni truly seeks reform (his recent policy document while better than many previous ones, is still a bit of a “mixed bag”), he appears to be seriously fenced in by political constraints.

Such a state of affairs is highly counterproductive and hampers steps toward improving the functioning of free markets, commerce and entrepreneurship.

The budget’s logic

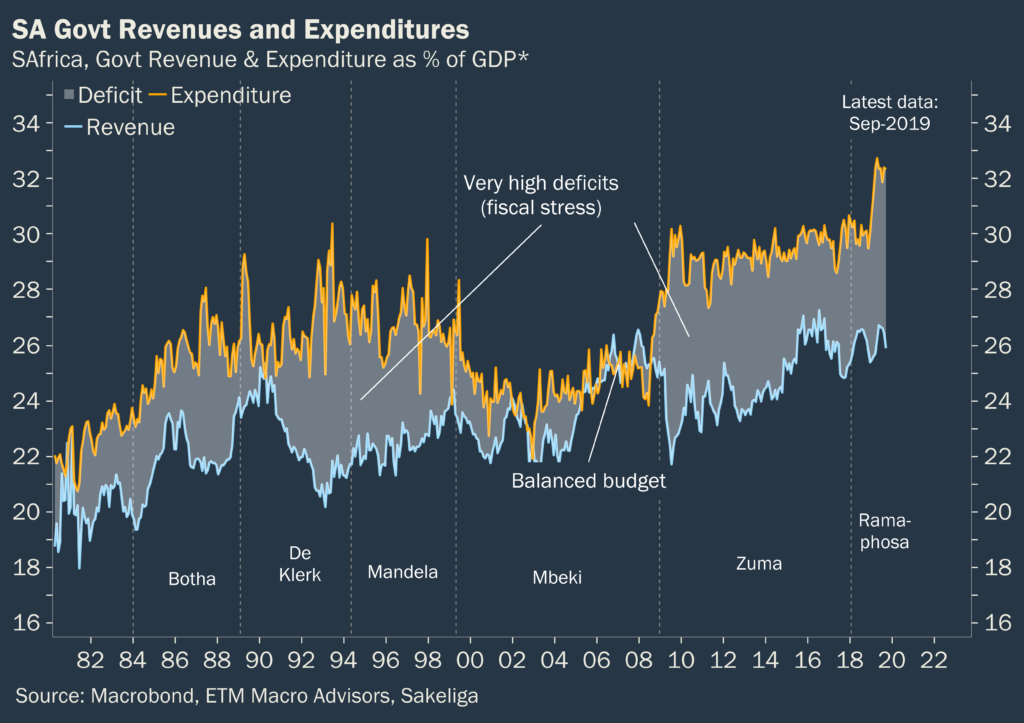

The logic behind the budget, it seems, is that a careful “balancing act” of new tax measures and slower rates of increases in spending will be sufficient to curtail the fiscal deficit over time. The reality is that fiscal stress in South Africa (see chart below) has steadily been increasing over several years. Projected fiscal stress is now even higher under president Ramaphosa than it was for most of former president Zuma’s term.

The budget deficit is driven by strongly vested “political claims” on the tax-dependent fiscus. Political promises, as they always do, fix expectations that drive spending. If these expectations are unrealistic, the likely risks obviously increase.

The genie of state spending, as it were, is entirely out of the bottle. Examples include “fee-free” higher education, expectations of above-inflation increases in government salaries and “free” healthcare (NHI) among others. Minister Mboweni faces a number of such virtually “untouchable” government spending priorities. These priorities, of course, were shaped by politics in the first place — these won’t be curtailed without some serious pushback.

In the end, the October budget foresees marginal cuts that don’t sufficiently address the pressing fiscal realities. Reductions in spending, we argue, need to be much more far-reaching. The MTBPS’s reality is one of substantial (even unsustainable) government expenditure (~ 32% of GDP), poor and questionable spending of large sums of taxes and a tiny tax base on which the entire structure rests.

To top it off, mounting legislative brakes and hurdles in the way of free commerce and entrepreneurs are still a reality in many sectors. Numerous sectors of the economy foresee more heavy state-involvement, which creates perverse incentives at the expense of market freedom. Sectors such as the property sector are already subject to even deeper anti-market intervention.

Is it then really any surprise when the fiscal reality of debt, deficits and weakening tax collections only seem to be getting worse?

The MTBPS itself brings little that is new. Many analysts foresee tax hikes in the 2020 budget, which is not a big surprise. Nevertheless, the reality is that we may have crossed the tipping point where new tax hikes are unlikely to contribute much to revenue. Additional tax hikes, however, never come without some economic trade-off. Hikes, in our estimation, are becoming increasingly expensive in terms of economic activity – perhaps even from the government’s own perspective. In the end, ever higher taxes are an unlikely contender for a “pro-growth” economic policy.

Eskom

Despite the new proposals, the Eskom crisis continues. The budget confirms further support to Eskom, which on appearance will continue it seems ad infinitum to be at least R23 billion per year for the next ten years. Eskom requires serious reforms and privatisation, but these are opposed tooth and nail by certain organised labour groupings. Minister Mboweni called for more stringent controls on Eskom, something we’ve all heard many times before. Moreover, Minister Mboweni, I am sure, knows that whether one calls it a “bailout”, or a “loan” the effect is the same if Eskom cannot pay.

Legal separation of Eskom is presented as a solution, but will take time, most likely longer than estimated. It is not without risk. Legal separation isn’t a magic bullet either. The core issue is whether the separation will introduce market-forces, valid prices signals, entrepreneurial insight, private capital formation and reduced moral hazard in the electricity sector. Without the discipline of market-forces, the legal separation of Eskom may amount to nothing more than mere window-dressing.

Payrolls

While the minister is calling for cutbacks in the state’s payrolls, if effect, the medium-term budget only reduces the rate at which the state’s payrolls would have grown. State-payrolls require more serious cuts, perhaps even in real terms. However, cuts of any meaningful order are not on the cards without some serious labour conflict.

Lastly, Minister Mboweni mentioned the Treasury’s policy paper and reforms, such as tourism promotion, the cutting of red-tape and reductions in regulatory burdens, and allowances for small-scale power projects. These might be good and well, but the underlying problem, we think, is the command-system that presumes excessive state involvement in the business sector in the first place.

Government officials frequently note the need for growth (but qualify it with the term “inclusive”, which of course still denotes state-intervention, even into the form growth itself should take). Many officials remain largely tone-deaf to the counterproductive nature of harmful policies they impose on or intend for the private sector. To state it simply, unwise, costly and harmful state policies really do undermine economic prospects.

To solve South Africa’s mounting economic crisis, the State, in fact, needs to be more “hands off” with the economy. It needs to reconsider policies such as BEE, AA and other centralising command structures and regulation, which hamper peaceful and productive economic activity. It also needs to stop approving new anti-market policies.

Minister Mboweni seems to grasp the potential of markets, to some extent. The challenge however is to get his party and other vested political interests to agree, or at the very least, to get out of the market’s way.